How I Discovered My Own Body Positivity At 50

Trigger Warning: The following article contains discussion of eating disorders, which some readers may find upsetting.

It started when I was 15. Instead of being a size 10, I was a size 11. My best friend was a 10 and had large boobs, so the boys tripped over themselves to ask her out. I shrugged it off at first, but as I crept up to a size 12 and then 14 my confidence began to slide downwards.

I was philosophical at first – the type of guys who went for me were the type I want to go for me, they are interested in the whole person and not just the looks.

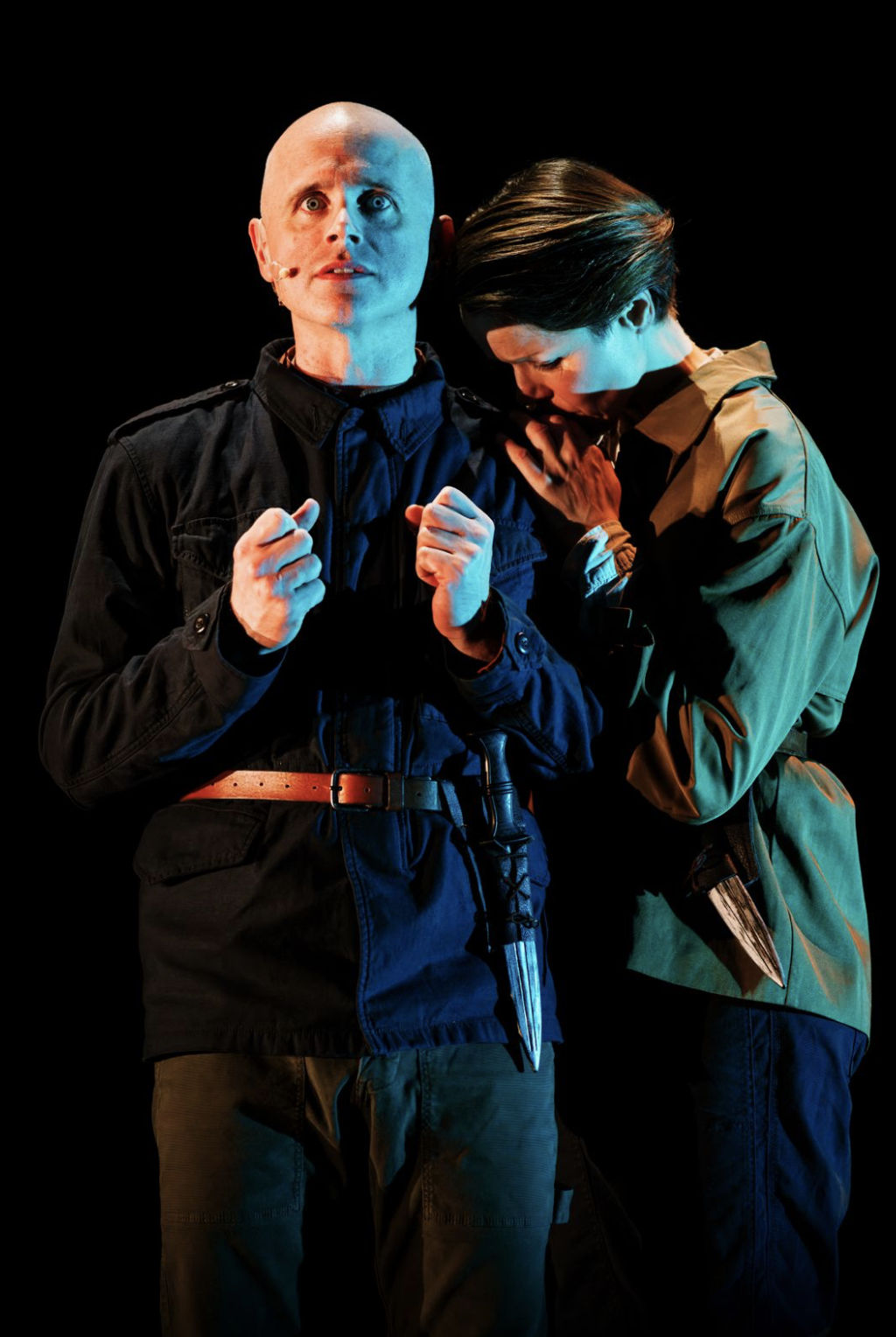

(image: Kirsteen Coupar)

I was attractive but I felt enormous. I had my pick of men, but that didn’t seem to matter. Everything around me was telling me that I wasn’t the right shape, that I wasn’t good enough.

I’ve been a feminist, an active one, all my life, and so it still makes me red-hot foot-stamping livid to know I was unable to fight against the onslaught of images and objects that assailed me from childhood. I was never a conventional girl. I didn’t wear skirts or dresses. I have never played with a doll in my life. I liked to climb trees. I fought to have an all-girl five-a-side team in school when I was 10.

But the expectations society has – has always had - on women permeated my skin and became part of me. I was unable to rid myself of it.

I threw up daily for ten years between the ages of 16 and 26. I wasn’t slim enough, I thought, and I comfort ate when I was depressed. I learned that the worst thing to throw up was spaghetti as it could get caught in your throat and that drinking Diet Coke helped to dissolve the food in your stomach so it was easier to move it up your oesophagus and into the toilet. I fasted and went on diets and I believed that nothing tastes as good as skinny feels.

And then I went to the doctor and told him what I was doing. It was terrifically hard because bulimia had become a friend, a relief, and to share it with the intent of stopping filled me with conflict. I got the help I needed, and I stopped, only backsliding a few times a year when I had overeaten and felt so uncomfortable I couldn’t bear it.

That was my 20s. Let’s fast forward to when I had kids at age 38: two in two years, with both pregnancies incredibly difficult. I crept up dress sizes stealthily, barely noticing it myself until I was a very apple-shaped size 24.

I was a missing mother. If you look through our photographs over the last 14 years, I’m absent from 99.9% of them. I was always behind the camera; if I ventured to the front of it, I found I hated the photographs that were taken.

I knew that people viewed me as obese and to many that equated with lazy or weak-willed. Yes, I was a senior executive, a volunteer, a single mother of two, a sole mortgage holder and a good friend. Yet I felt this judgment when networking and when interviewing. It drifted across me like smoke and settled. I could not shake it off.

I joined dating apps and talked to men, but when they asked me to meet them in person I chickened out. All my photographs on those sites were headshots. I’m sure they could tell I was overweight, but not by how much. The thought of them meeting me and finding my size repellent was enough to ensure I never followed through. I would delete apps then add them again months later, but the same thing would happen.

Then came Iceland. Once an ardent traveller, I had cooled my heels while the kids were smaller - but now they were 11 and 12. I planned a 14-day trip to Iceland; we were to drive every day and stop in a different Airbnb each night. I decided I had to come out from behind the camera and be present in our photographic memories. It was hard at first, joint selfies with me trying to position myself behind the children so less of me could be seen, but then I found that silliness made it easier. Perhaps I was sticking my tongue out at society.

At 50 I found myself suddenly unemployed in the middle of a pandemic. My daughter was constantly on TikTok, so, remembering Parenting and the Internet 101, I downloaded the app to check whether it was appropriate.

I went down a rabbit hole and came up two hours later; it was hard to pull myself away. For two weeks I watched and I found a wealth of body positivity. There were girls and women showing off their gorgeous plus-sized bodies in the clothes they actually wanted to wear.

I had been dressing to camouflage myself for years: black because it was slimming, and longline tops to hide my stomach. I was scared of colour because I was sure it would draw attention to me and I just didn’t want anyone looking. Buoyed by the confidence of my TikTok sisters, I started making my own video content based on personal experiences. It took off.

Two years earlier a man had tried to catfish me on a dating site. I realised within a few messages as he told me about his dear departed wife, his quest for a new soulmate and his lonely motherless daughter. I decided to play with him so for two months I said ridiculous things – I called him ‘my lobster’ as an endearment, shared with him I had kidney failure and needed a transplant, and pretended to be a concerned friend who didn’t believe that he was being honest.

It was a hoot. I made a series of TikTok videos and told this story. After the first few went up I braced, knowing that the internet was full of people who like to troll and criticise. I just hoped the positive comments outweighed the unpleasant ones. But there were no trolls. Instead, there were hundreds and then thousands of people telling me I was funny, that they loved to watch me, that I was gorgeous, that I had amazing eyes, that they couldn’t wait for the next video.

Suddenly I felt like I had stepped out of the dark. They didn’t care that I was ‘morbidly obese’; they cared that I was telling a good story and entertaining them. They were looking for the good things about me in a way that I had forgotten to.

I’m at nearly 75,000 followers and my most popular TikTok video now has 1.7 million views. My confidence has soared. I went on a dating app and got talking to a nice guy; he asked me out for coffee and I said yes. We met, and we chatted, and it was good. At the end of the date, he hugged me and said he would like to see me again.

I’m out there in the world. It’s still a process, but as Nina Simone says, I’m feeling good.

Beat promotes awareness and understanding of eating disorders, visit their website (www.beateatingdisorders.org.uk) for more information. They have a dedicated Youthline for those under 18 (0808 801 0711) and helpline for those aged 18 and over (0808 801 0677).

Help us keep the City Girl Network running by supporting us via Patreon for the price of a cheap cup of coffee- just £2 a month. For £3 a month you can also get yourself a Patreon exclusive 10% off any of our ticketed events! You can also support us by following us on Instagram, and by joining our City Girl Network (city wide!) Facebook group.

Written by: Kirsteen Coupar