Feminist Perspectives on Hormonal Birth Control

Note: The following article contains discussion of depression and anxiety, which some readers may find upsetting.

After over a decade on hormonal birth control I decided it was time for a break- the combination of my IUD’s time being up, not having experienced a natural menstrual cycle in ten years and flying solo at the start of a pandemic pushed me to the decision. It was time to see what my mood, body and cycle was really like sans hormones.

In a world where women’s reproductive rights and access to birth control are under threat, it is a luxury to examine the choice of taking birth control at all. Choice and bodily autonomy is engrained in feminism and the accessibility of birth control must be safeguarded and I’d never discourage folk from finding a method that works for them.

I’m not anti-hormonal birth control and find the trend of wellness bloggers condemning anything but ‘natural methods’ troubling, fraught with privilege, breeding unnecessary fear. Many find hormonal contraception suits them and see positive effects on physical and mental health, particularly in premenstrual conditions such as PMDD.

Yet for someone avoiding pregnancy, finding something long-term and effective, if you’re not up for barrier methods, can be an arduous, grim task: a Russian roulette of side effects. For example, since sixteen, I tried four different oral contraceptives, which caused low mood, fogginess, and migraines, before getting the Mirena IUD, which proved largely straightforward.

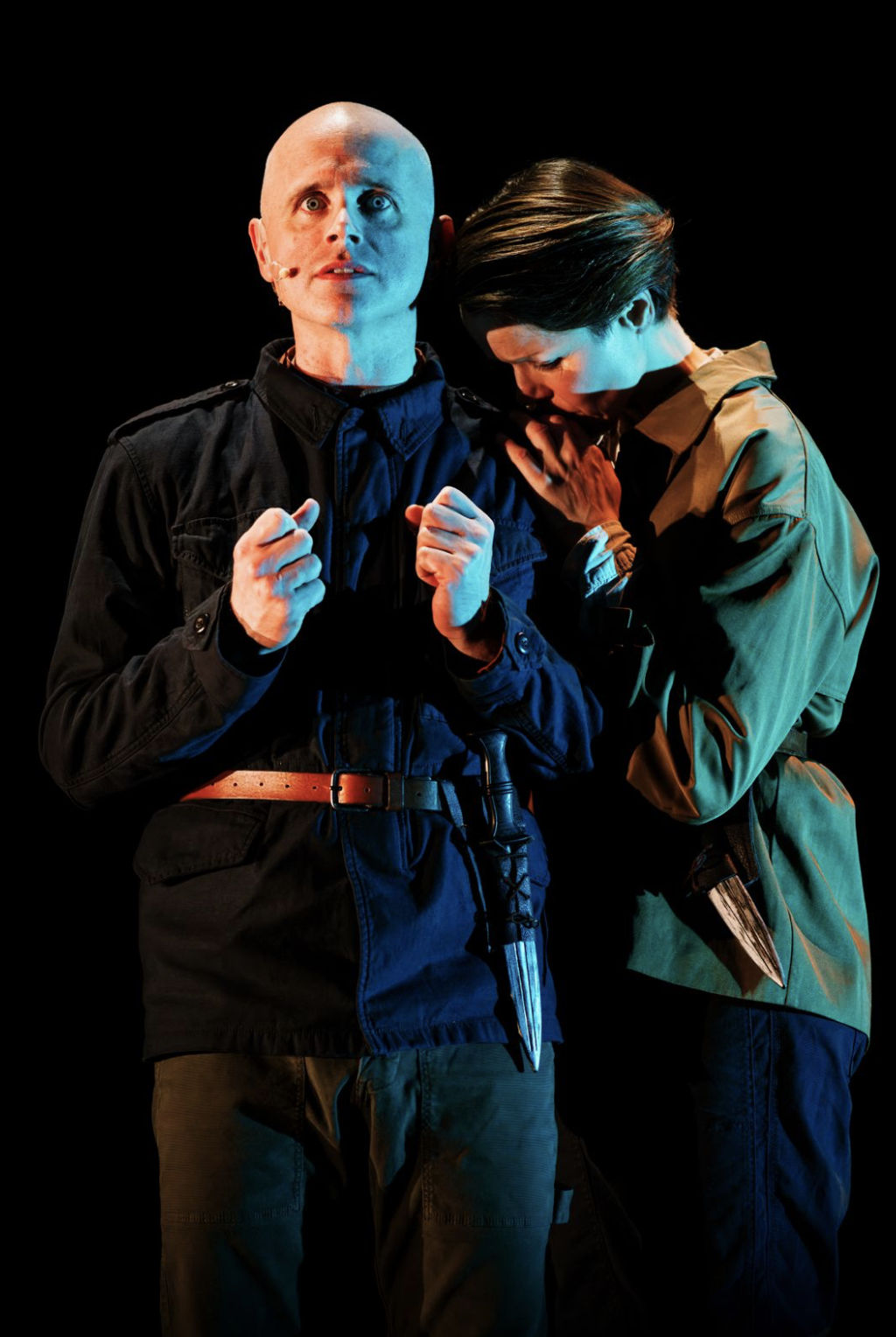

Unsplash: Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition

Historically, negative side-effects are the price women have paid for bodily autonomy since 1957 when a US study dismissed women’s experiences of dizziness, blood-clots and nausea on the Pill. The medical establishment continues to undermine women’s suffering- women’s pain is still frequently discounted as non-existent, and psychological distress dismissed as over-sensitivity.

Given that the pill has been seen to correlate with depression in up to 16 % of women, and other hormonal methods associated with an increase in mood swings, anxiety and low mood, particularly when there is a history of psychiatric illness, it seems health professionals urgently need to take patients’ experiences more seriously.

‘Merely’ physical side effects such as acne, migraines and weight gain shouldn’t be seen as unavoidable trade-offs for reproductive freedom. Often it can feel like a toss-up of how much you’re willing to tolerate for bodily freedom and peace of mind.

Conversely, hormonal contraception is also being marketed as a lifestyle drug-with the bonus of reducing risk of pregnancy- a means of clearing skin, increasing cup size, skipping PMS. In the US the pill Yaz is sold with the tagline: ‘Beyond Birth Control’, endorsed as ameliorating the ‘inconvenience’ of menstruation and associated acne, headaches and moodiness.

This emphasis on freedom from menstruation is significant. Clearly, menstruation is not essential for womanhood but its dismissal as a drag within the patriarchy is politically loaded. The menstruating body is abject, incompatible with neo-capitalist pressures of containment, productivity and curated #authenticity. Birth control, thus, is interwoven with external pressures

Undoubtedly hormonal contraception has given women freedom, yet its burdens exist within a culture that subjugates women and requires them to bear these discomforts to prevent pregnancy. Recently a beau, wrestling with a condom, grumbled: “God, wish you were on the Pill. I’d take it if it was an option”. “Sure,” I snapped back, “you couldn’t handle the side-effects”. .

Research backs me up on this point, clinical trials for a male contraceptive were abandoned due ‘intolerable’ side effects of ‘nausea, weight gain, acne’, identical to those for existing female birth control. It seems women are expected to put up with this whereas men won’t stand for it. This asymmetry, if you’ll pardon the pun, is a bitter pill to swallow.

Coming off hormonal birth control after a decade has been a positive experience overall. I’ve felt more ‘me’: clear-headed, connected to my body, rather than the slightly dull, disconnected sensation I’d been accustomed to.

My period returned three months after the removal and although the monthly rollercoaster of energy, emotions and sex-drive has almost been a second puberty, but I’m happier knowing these peaks and troughs are mine.

No, I’ve not missed cramps or mood swings, but life with a period isn’t crippling as I feared. Through reading about my cycle, I can now recognise there are weeks when I’ll feel like Beyoncé (ta, peaking oestrogen) and others I’ll need more rest. In a society that prioritises incessant productivity, respecting my body’s cyclical needs feels borderline radical.

We would encourage anyone identifying with the topics raised in this article to reach out to organisations who can offer support, such as Samaritans on 116 123 (www.samaritans.org) or Mind on 0300 123 3393 (www.mind.org.uk).

Help us keep the City Girl Network running by supporting us via Patreon for the price of a cheap cup of coffee- just £2 a month. For £3 a month you can also get yourself a Patreon exclusive 10% off any of our ticketed events! You can also support us by following us on Instagram, and by joining our City Girl Network (city-wide!) Facebook group.

Written by Hannah Stephings