Bridgerton: Irresistible, Refreshing… Flawed?

Scrumptiously playful, utterly preposterous – but irresistibly moreish. Bridgerton is not without its flaws, but at its heart is a refreshing glimpse at what a period drama can be when corset strings are loosened.

Bridgerton is a raucous, romping spectacle. Shonda Rhimes’ playfully indulgent series is unapologetically silly – yet also broadcasts some reverberating truths. What I enjoyed – and believe me, one cannot entirely decipher if one is overcome with mindless joy or contempt when one watches Bridgerton – is how Rhimes’ series refuses to take itself too seriously.

Bridgerton is at its best when it dishes scintillating playfulness, relinquishing the conventions that typically confine a period drama and allowing us a glimpse at what a costume drama can be when it loosens its corset strings and unbridles itself from historical accuracy.

And the result is simply fun, for the most part. As the pandemic continues to curtail our existence, Bridgerton with its exuberant erotic and aesthetic qualities is the simple fun I didn’t realise I needed. I binged the season in a matter of days and the experience was a bit like scratching an insatiable itch; a slightly uncomfortable sensation that I could not, despite my best efforts, stop. The series is utterly ridiculous and clichéd – but nonetheless, irresistibly moreish.

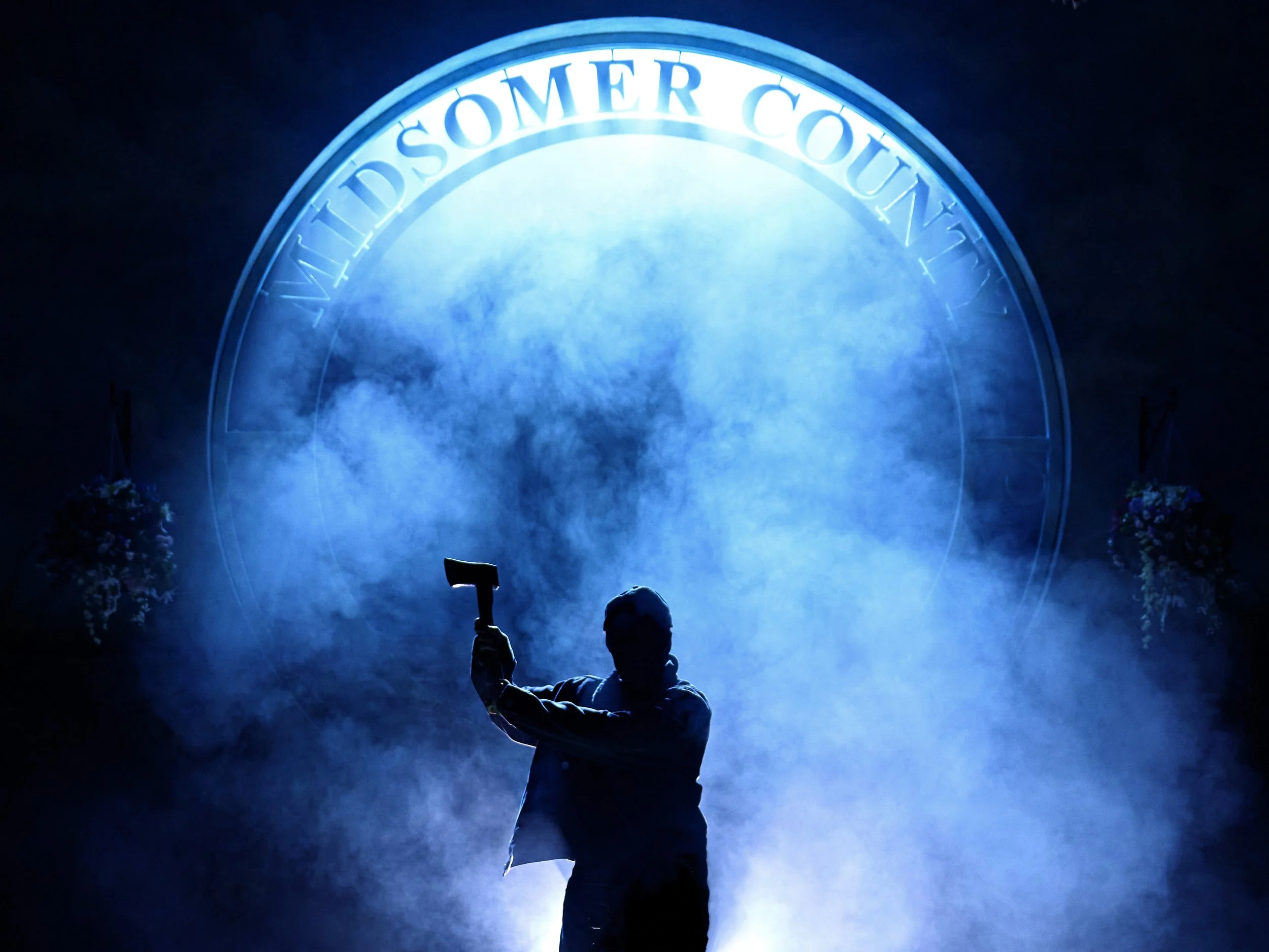

Set in 1813 London, Bridgerton is based on the romance novels of Jane Austen superfan – Julia Quinn. It’s courting season on Grosvenor Square and every well-to-do family in London’s high society (aka the ‘ton’) is preparing to present their daughters to Queen Charlotte (brilliantly played by Golda Rosheuvel).

Viewers are welcomed into Regency rivalry at its peak – as young women are decorated in feathers and florals alike and dangled as bait in order to dazzle the prize fish (in this case, eligible and debonair bachelors). At the centre of the competition, the Featheringtons and the Bridgertons – and the mysterious, rousing and unknown Lady Whistledown, whose weekly gossip column stirs the tons-folk and commands events.

Whistledown’s scandalous tongue n cheek column is narrated by none other than Julie Andrews herself – her proud and tattling voiceover perfectly mystifies the ridiculousness of this would be Georgian Gossip Girl.

The show bursts with juicy elements – fistfights, hushed gossiping, rampant bonking, double-crossing, betrayals and secrets – it’s full of scandal, deceit and stupid men- riveting. The Shondaland production team clearly relished creating this ramped-up world of privilege, and the result of casting Regency London through American eyes is Downtown Abbey on steroids – a pastel-erotic acid trip.

The decadent estates, bountiful bosoms, gleaming gardens, panting sexual tension and luxurious gowns of satin, velour and velvet - it’s visually fantastic, indulgent and captivating. Overblown production has few limits – and Shondaland’s producers dared to sway so far from historical accuracy, sound-tracking the series with classical renditions of Ariana Grande and Billie Eilish.

Caring not for the finer points of critical reality, the cast is refreshingly aware that instead of being entrusted to faithfully re-enact British history, they are freed to create binge-worthy entertainment. Chris Van Dusen (the show’s Showrunner) provides a blueprint for what British period dramas can be freed of historic code – paving the way towards more inclusive representation and offering people from all racial backgrounds a visual world that doesn't centre whiteness.

Bridgerton’s casting diversity and departure from the racial homogenous casting typical of period dramas are the series most immediately striking qualities. Van Dusen reimagines 19th century London with Black aristocratic characters such as the (very much admired) Duke, Lady Danbury and Queen Charlotte.

In Bridgerton Black characters are integral to the social caste system of Georgian society, take the working-class Mondrich family, Madame Genevieve and Marina Thompson. Here is a costume drama in which people of colour are not erased or cast solely as victims of racism.

Bridgteron purposely pushes back against the racial homogeneity in the casting of the likes of the Crown and Downton Abbey. Gareth Neame, Downton Abbey’s executive producer, insisted that historical accuracy was imperative to the show’s production. According to Neame “we can’t start populating the show with people from all sorts of ethnicities.”

Evidently, accuracy police such as Neam roam far and wide – asserting their right to produce period dramas that are as whitewashed as British history books. Under the guise of accuracy, particular roles will continually be denied to people of colour. What this really means – is that accuracy becomes synonymous with exclusivity and leaves slim pickings for people of colour.

There is a real demand for stories about the Royal family, about war – about the general past. If production teams continue to debate whether fictional characters can be played by people of colour (Hermione Granger and James Bond to name two examples) and cordon particular roles off, then our TV and films will be as whitewashed as our history.

Bridgerton provides a vital blueprint for costume dramas moving forward, allowing people of colour to thrive in the qualities that make the genre so appealing without having to be servants or enslaved. Rhimes’ does not ask audiences to suspend their racial preconceptions and accept a colour-blind world. Rather, characters understand Blackness as one of many facets of their identity.

That being said, Bridgerton has its blind spots. To say that the series is the height of representation would be wrong, it’s handling of the subject can feel haphazard and slightly superficial. Race is practically ignored, aside from a two minute conversation between the Duke of Hastings and quick witted Lady Danbury which suggests that the King marrying a Black woman removed racial inequalities; “we were two separate societies divided by colour until a king fell in love with one of us.”

Most of the characters of colour in Bridgerton suffer from a lack of attention, agency and context outside of their relationships to white characters. I for one wanted more from Queen Charlotte’s story and felt that her tale of a Black woman trying to rule the country alone could have been more than an awkwardly paced backdrop. I think Lady Danbury is the only Black character you didn’t feel pity for.

The vast majority of speaking roles belong to white characters and Black characters are undeveloped – reinforcing the white privilege that the show attempts to undercut and failing to move the white narrative from the spotlight as I thought it might. The series avoids the abolitionist movement that began to flourish in 19th century Britain – tending towards entertaining escapism over explorations of real-time dynamics.

Despite its shortcomings, Bridgerton is an imperfect step in the right direction. The series testifies to the fact that it takes little imagination and effort to be inclusive, as opposed to the hard-pressed efforts that uphold a centuries-old industry built on the grounds of exclusion.

This lavish romance can feel shallow in substance at times – the tales of romance follow a familiar formula and the sequencing and plot can feel both overdeveloped and underdeveloped. But chiefly, Bridgerton is endlessly amusing fluff. A real page-turner, providing cheery escapism at a time where we most need it. Its language is accessible to all and it certainly doesn’t pretend at poetic elegance – the script is as playful, absurd and dazzlingly refreshing.

Rhimes’ spiritedly evokes the logistical problem of being a woman in 19th-century society, hiding the bump, discovering the birds and the bees, battling with chastity, depending on your period (how often do we see real blood!?) The elusiveness of sex really struck a chord – sexual education is still shockingly male-centric.

The series makes a point about keeping women in the dark about the realities and sensations of sex, elucidating this as a means of repressing them. As Daphne discovers, sexual knowledge and autonomy over one’s own body is power. The sex scenes often focussed on female perspective and pleasure, feel like subtly subversive proclamations of purpose. The portrayal of sex is definitely questionable in places but there is a refreshingly balanced gaze on both the male and female body.

Bridgerton recognises that strict social rules really do make people miserable, reassuring its viewers who likely sit at home amidst the raging of a relentless pandemic. As lockdown continues, Bridgerton quenched a thirst – not just the frothy, mindless fantasy of pleasure that we needed – but a pleasant reminder of what the genre should strive to be.

Help us keep the City Girl Network running by supporting us via Patreon for the price of a cheap cup of coffee- just £2 a month. For £3 a month you can also get yourself a Patreon exclusive 10% off any of our ticketed events! You can also support us by following us on Instagram, and by joining our City Girl Network (city-wide!) Facebook group.

Written by Polly Wyatt